The streaming giant currently known as Netflix has been widely believed to be missing the target more often than hitting it in the past few years.

After the decline in viewership of series’ like their hit Stranger Things, likely due to the fact that the seasons have such a long production time in between them that the entire tween cast is now deep into adulthood and ready to have children of their own, Netflix found their next big success with Bridgerton, and although it almost lived to enjoy the same hype and success as the aforementioned sci-fi series, it likewise declined in views after its lackluster third season, which also garnered plenty of criticism from fans and new viewers alike, although this writer cannot for certain express any pleasure or displeasure towards the series, as it was not, dear reader, created with the likes of me in mind. I have tried, and failed, to enjoy it, but the first book left such a sour taste in my mouth it resulted in my inability to divorce the two products, having gotten only one or two episodes deep into the second and third seasons, and nearly finishing the first one, had it not been for the, surprisingly less explicit than in the novel, rape scene involving Daphne and the Duke.

Regardless of all this, however, a recent sitcom by the streaming giant has gained the attention of many a viewer, such as myself, and perhaps it may even sway some people’s opinions as to the decline of Netflix, and, hopefully, usher in a new era of art for the streaming platform.

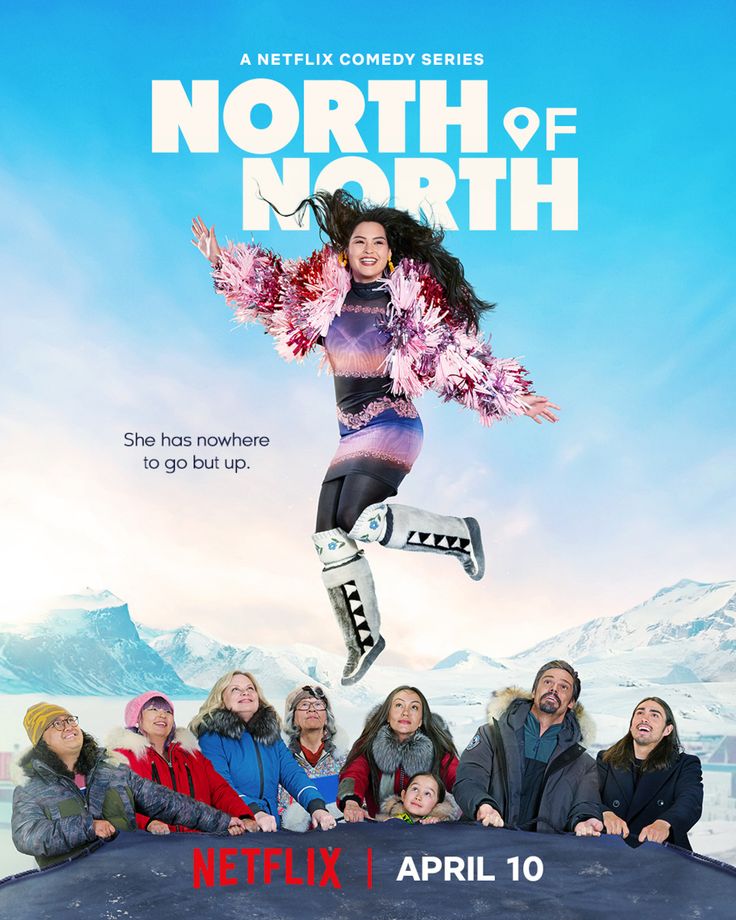

Allow me to introduce North of North.

North of North hails all the way from Canada, and is the baby of Inuk creators Stacey Aglok MacDonald, a film and television producer from Nunavut, Prince of Wales Island (the place where the series takes place) and Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, a filmmaker known for her work on Inuit life and culture, and owner of Unikkaat Studios, a production company focused on producing Inuktiut films. All this to say, clearly this cake was baked by professionals.

Totalling 8 episodes (not nearly enough to saciate my hunger), this quick-to-binge series tells the story of Siaja, played by the drop dead gorgeous Anna Lambe (who is my age????), a young Inuk woman who married straight out of highschool, had a daughter, and has dedicated the past 8 years of her life to caring for her family as a wife and homemaker. Everything changes, however, when, after confronted by the fact she wishes to have a more independent life and career, she ends her marriage by causing a scene at a public event and earns a target on her back from her traditionalist tiny Arctic community.

The series is a gloriously funny and relatable exploration of womanhood, self-love and building community, as well as a first of its kind in portraying the lives of Inuit as main characters with ups and downs, flaws and qualities, raw and human just like anyone else – without imprisioning them in stereotypical roles of wisdom, victimhood or villainy.

Another positive of the series is the fantastic cinematography. North of North is filled to the absolute brim with gorgeous and creative shots of the Arctic, showing the reality of living amogst the ice is much more beautiful than anyone could imagine, which we are also reminded of by the constant remarks made by the characters about the gorgeous scenery. And it is, indeed, gorgeous. Throughout the series, we are shown how beautiful the cold Arctic can be, even if it is dangerous, especially because it is dangerous. There’s a mixture of beauty and treachery in the untouched wilderness of the Arctic, protected only by those who truly appreciate and understand it.

–

Two things which stand out as quintessential for the series are the focus on indigenous culture through dialogue and, most importantly, costuming. The storytelling embedded in the costume design of the series is perhaps the most eye-catching, but we also see, and hear, the characters converse about their culture in a way that is both natural and requires no further explanation, making the approach flow easier and without feeling exploitative or overly stiff.

The one time we do get an explanation of cultural background is during the baseball episode, when we are treated to a little YouTube video with the information necessary to understand the specific rules being played by. But even the video comes with such ease and naturality that it would be difficult for any viewer to question its presence in the episode, even if it may at first seem like a deviation from the previously established narrative flow, the entire series’ humour is so human – in its way of approaching its content with the same seriousness, or lack thereof, that we approach life – that the video may come out of nowhere, but it fits right in with the other more outlandish shanenigans we witness.

As for the costuming, of course, Siaja’s takes center stage, but all the Inuit characters are so well explained through their costuming, it does genuinely sell the idea that this is just how they dress, instead of giving the impression that the costume designers were fighting each other for who can catch the viewers’ eyes the most, as if they need to trick the viewers into believing the series is good based solely on how elaborate the costuming is – a feeling I often had with the most recent season of Bridgerton (of which the costuming has become a parody of itself), as well as the aggressively 80s choices of the latter seasons of Stranger Things.

A beautiful positive equally comes from learning that all the costumes in the series are a product of slow fashion, carefully crafted by hand by Inuit designers and dressmakers, full of love, culture, tradition and magnificent colour.

According to the costume designers, Debra Hanson and Nooks Lindell, they focused on local Inuit artisans and designers to source the clothing, shoes and jewellery worn by the characters.

“It was really important to us that our parkas and anything traditional were made here in Nunavut, by Inuit artists,” said Aglok Macdonald. “They had to go to the ends of the Arctic to fashion the magnificent costumes that people will see on screen, which are unlike anything that’s ever been seen before.”

And although her entire wardrobe is enviable, Siaja’s earrings are likely some of the best piece of character design in contemporary television. They are vibrant, full of life and tell the story of not only our main character, but of her birth, her community and her family. The Inuit designs are colourful and fun, and she seems to match her earrings to her clothing, revealing a fashion-forward creative spark that we see bleed into her work throughout the series.

Her clothing is also a form of self-expression, being particularly important as we further witness her husband’s verbal and emotional abuse, and understand her feeling of living in her husband’s shadow, especially as the town considers him, Ting, as the ideal golden boy, and her simply as his wife, we truly see Siaja grow into herself and her own skin as she incorportates colour and culture into her wardrobe, taking back the confidence and acceptance her husband took away from her so many years ago.

And speaking of characters, although they will be hard to summarise, the entire cast shines in their personal roles and brings to life a vast array of diverse indigenous characters never before seen on screen.

Anna Lambe, who grew up in the town of Iqaluit, where the series was shot, noted:

“People constantly came up to hug me and say how proud they were of me and how exciting this was for Nunavut, for Inuit and Indigenous film and television. I wouldn’t have wanted to film it anywhere else because the outpouring of love and support we received was so empowering.”

Empowerment that which her character also received throgh the series, finding out who she truly is and realising what can be changed and improved, as well as what she’s capable of, and touching on one of the main philosophies of the series, the anxiety with which young people live believing it is too late, there’s no longer any time, and it is impossible to start over. Through Siaja, who’s lived experiences befitting a much older woman, having to first care for her mother through her alcoholism then care for her husband and child, all while not even 30, we see that reinventing oneself is an integral part of life and living, and we must not allow our past experiences or pain to dictate how we live and create our future. It’s a warm and fuzzy lesson many people my age and even younger need to learn in this day and age where it seems your own vision of success can only hit you once at the ripe age of 20 then nevermore.

On a different note, more than the costuming and cinematography, the fluidity of the acting in the series is truly mesmerising. Through Anna Lambe’s Siaja, we can see and understand facets of the human condition not quite so easy to portray or represent, and that would only flow so well in a series like North of North. More than just representing her culture, Lambe helps to beautifully bring to light the power of community, and the beauty of being someone who can understand others and wholeheartedly cares about their needs. Siaja demonstrates time and time again that she is, genuinely, joy incarnate; a bright sunlight illuminating those around her, the warmth that may be missing in the Arctic burning bright inside of her heart. She can truly become one of the most inspiring contemporary representations of womanhood: kind, empathetic, smart, creative and, most importantly, self-aware; not only a portrayal of the “modern Inuk woman”, as she puts it, but of the type of womanhood humanity has depended on for survival since the beginning of time.

It truly surprised me how much this series has endeared itself to me. It’s very much out of my comfort zone, as I’ve watched the odd sitcom every now and then, but nothing this recent, and I do believe some of its charm comes from the ability to capture the best parts of classic sitcoms, but the rest is all up to the amount of passion and dedication the viewer can sense bleeding from the screen, making the series a true labour of love.

And it is this thoroughly human portrayal of womanhood and life in community that brings me to the only aspect of the series I have become dubious about whether or not I enjoyed: Ting.

Ting is Siaja’s (now ex) husband. They met in high school, got married the second they graduated and had a daughter together, Bun. Ting is also the town’s golden boy, being a hunter like his late father, and being seen as the model Inuk man.

In one scene, during a fight with her mother, Siaja admits she married Ting straight out of high school as a means of escaping her home life and not needing to be there to care for her alcoholic mother, but it comes as no surprise that she then ends up caring for her husband and daughter in nearly the same way throughout her marriage, making her stuck in a cycle of living for others while watching her own self disappear.

It’s unclear whether Ting knowingly uses her weaknesses to exploit her or whether his exploiting comes from his need to feel superior due to his own insecurities and trauma related to the loss of his father. However, in the beginning, it seemed to me there was a disconnect between what we were watching as the audience and what the characters could see and how they reacted to Ting’s treatment of Siaja, as he is very much a verbally abusive and controlling man, with Siaja even mentioning in the early episodes that she didn’t go to parties a lot since she graduated because her husband “wanted her all to himself”, speaking to a much deeper controlling side we witness throughout the series.

In the first episode, Siaja falls overboard during a seal hunt and nearly drowns in the cold waters of the Arctic, being rescued by her husband and brought to shore, and, while he parades in the glory of his act of bravery in saving his wife’s life, when they are alone, he belittles her for making him look like a fool and a bad hunter, stating she humiliated him.

This sort of behaviour is repeated throughout the series. He constantly tells Siaja she would never find anyone better than him, that she’s incapable; and when Siaja confronts him with the promise he made of allowing her to go back to work once their daughter was old enough, he surprises her by revealing he agreed to adopt his cousin’s baby without telling her with the implicit understanding being that Siaja will be the one to raise the child.

These insults seem to only happen, at first, when they’re alone, but they soon escalate to happening in front of witnesses, like their duaghter or Siaja’s mother, driving the viewer particularly insane since Neevee, Siaja’s mother, is constantly insisting on their staying together and warns Siaja that being a single mother is a lonely life, going as far as punishing her for asking for help with Neevee’s granddaughter in a bitter spiteful scene that screams “because nobody helped me, I won’t help you”. These scenes serve to remind the viewer that Siaja is above repeating the cycle of violence she was raised in, but also highlight how brave the main character is for choosing to build and care for her community even if they have done nothing but diminish her and her mother due to her being the daughter of an unmarried woman.

But Siaja is human, and particularly emotional due to her precarious childhood, therefore easy to manipulate, and by the last couple of episodes, Ting has realised this is a way he can win her back, seemingly having “changed” by acting like the perfect family man she wished he was, listening to her and getting her gifts, telling her she can work, only to hide her phone once he spots a text from Kuuk, the adorable love interest, showing her his ways have not changed.

This is what leaves me puzzled. Siaja doesn’t go into detail about her married life to her friends, hiding the more harsh comments and criticisms of her husband towards her, which insinuates she understands these are bad behaviours, but even when these things happen in front of others no one is willing to call a spade a spade and label this man as an abuser, which becomes increasingly frustrating to watch, until I realised maybe this is the goal – a realisation that didn’t make it any less frustrating to watch, but at least gave me a slight sliver of inner peace.

Siaja comes from a highly conservative and traditional tiny community. She’s been ostracisized for not being particularly bright or succesful, told to hide behind her husband, and suffered the consequences of having a mother that didn’t conform to what’s viewed as being a well-adjusted woman – having a husband, a home to care for, kids (in that order). Of course those around her, particularly older people, will not recognise Ting’s behaviour as abusive, and even those who do might not wish to point out said behaviour as a abusive since it is none of their business what happens between a married couple. But the series still wishes the audience to be aware of how much of a facade Ting’s behaviour is, and hopefully because said behaviour will be further exposed and explored in the upcoming season – if there indeed is to be one.

One bit of dialogue that changed my mind about the intentions behind Ting’s charactirisation, particularly when he’s around others, comes near the end of the season, episode 7 “Lost and Found”, where Siaja considers the idea of getting back together with Ting after he seems “changed” during his recovery from the injuries he sustained while lost in the depths of the Arctic during a hunting trip. Her friends point out that it took her 7 years to leave him, but only a few days to come back, bringing up a known fact about abuse victims and how it takes, on average, 7 attempts for a victim to fully leave their abuser.

This seems like confirmation of the series’ awareness in regards to Ting’s treatment of his wife, as well as showing that some people, while aware of their struggles, might not feel completely comfortable pointing them out due to their environment.

An environment that also fostered the series’ most interesting and the secondary most important relationship, only being surpassed by that of the main character with her own self: that of Siaja and her mother.

Siaja juggles the love she has for her mother, who raised her alone in a community where single motherhood is very frowned upon, with the resentment she harbours for having her youth stolen by being forced to care for her mother through her substance abuse.

They oscilate between loving kindness and understanding, then big blowout fights, where it becomes clear Neevee has severe emotional issues and refuses to own up to her failures, or indeed acknowledge them outloud, as well as failing to admit when her actions hurt others, with the old-as-time excuse “you’re so sensitive, in my time we had it even worse and never complained” often in use throughout the series. She comes off as a “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” type of person, a common character trait in ethnic parents, especially those who have had to fight for survival and refuse to recognise that their descendants battles, although looking different from their own, are equally as important.

Neevee’s own character growth will hopefully reach its apex in the upcoming second season, but for now it seems she’s starting to recognise her own faults and identifying the need for self-improvement, thanks in no part to her own daughter’s fight for independence and acceptance.

Her character becomes essential in understanding the world the series is set in, since her life story and experiences mirror those of many indigenous women before her, belonging to a generation that saw the turmoil of the changing times while also experiencing the pain of the past. Unfortunately, it seems that not much has indeed changed for indigenous woman, a piece of knowledge that no doubt keeps Neevee up at night in fear for both her daughter and granddaughter.

Neevee mentions in one scene how she’s uncomforable in schools due to the history regarding Residential Schools, the last of which closed in 1997, meaning there is a big possibility Neevee herself, as well as people she knows, have fallen victim to the physical, sexual and emotional abuse that occurred in the state-funded schools, designed to strip Indigenous children off their culture and drive them away from their families by any means necessary.

The topic brifly comes back later in the series when Neevee discovers her own mother, who passed away when she was too young to remember her, went to Residential School with Elisapee, the elder, deeply religious and judgmental character who serves as a stand in for the more conservative side of their community.

In the second part of the series, Neevee became, surprising even myself, one of the most important and indeed one of my favourite characters in the series, not only due to how the show later begins to approach her story with the kindness it merits, showing facets of the woman unknown to everyone (including Neevee), in a series of events that culminates with Siaja coming to see her mother in a new and more humane light, although forgiveness may not be completely in the picture for them yet.

The series also touches, through Neevee, on a historical form of abuse against indigenous woman that is woryingly prevalent to this very day: the kidnapping of indigenous children from their mothers at birth or during early childhood, a type of violence which happens in many ways, such as through Residential Schools, framing parents for abuse or alcoholism, pushing indigenous communities into extreme poverty then blaming them for not being able to provide, etc; but in the series, Neevee confides to have “lost” her daughter to the child’s on father, having been kidnapped by the white man in early childhood and with Neevee never being able to locate her, culminating in her inability to confide in Alistair about the very existence of his daughter (Siaja) and driving him away out of fear of losing yet another child.

Of course, part of the fact Neevee and Siaja’s relantionship interests me so much is due to my own turbulent and confusing relationship with my mother, which is something I believe most, if not all, women can understand. The haunting knowledge that our mothers, however good or bad at their roles they might’ve been, were once defenseless and innocent little girls, stripped of their own agency and forced into pre-made boxes that didn’t fit them, made to become small, hungry, complacent; to forget their dreams and renounce their happiness in service of the “most important job they would ever have”, regardless of whether or not they wanted it or indeed felt ready for said job. The expectation placed on these women to accept a role they are supposed to be naturally wired to perform without payment, gratitude or human rights, creates a vicious cycle of little girls being raised by women who hated them, or who traumatised them in order to prevent them from getting as hurt as they once were.

The first time a woman sees her own mother’s humanity is when our world truly begins to crack, for recognising the humanity in the person who gave us life, recognising the lack of agency and forethought that might’ve gone into it, brings us an overwhelming sense of dispair which is impossible to describe to anyone who has yet to experience it.

–

This series spoke to me in ways I was not ready for.

More than just a silly sitcom, North of North is a portrayal of the good still left in humanity, and how we can prosper even in environments where it seems impossible. It is a beautiful, heartfelt series created with an enormous amount of passion and dedication, and I am truly happy to have experienced it.

Which brings us to my main, and possibly only, concern towards North of North: with the current market of streaming websites combined with the rise of conservatism in western culture and online bigotry, is Netflix ready to not only fund the further development of the series, but to stand by it when it eventually becomes the target of the “everything is too woke now” mob? Will Netflix understand the gem it has on its hands and continue to support it, or is the series doomed to suffer the same fate as other incredibly well-made series like The OA, Sense8, Anne with an E, etc., and get the boot once it doesn’t prove to be as profitable or socially acceptable as the corporation wished it would be?

Honestly, we have waited 10 years for the completion of Stranger Things, which cost Netflix more than the GPD of a small country (not exaggerating by the way), surely we can have a few more years of this wonderful little cosy community in the Arctic, right? Right?

Leave a comment